Research team produces first female bison pregnancy with sex-sorted sperm

When a wood bison cow gives birth at the University of Saskatchewan (USask) Livestock and Forage Centre of Excellence later this year, her offspring will be the first bison calf produced with sex-sorted sperm — a significant development in the revitalization of the threatened species.

By Lynne GunvilleThis latest collaborative project represents another research first for a long-term partnership between USask researchers and Dr. Gabriela Mastromonaco, director of conservation science at the Toronto Zoo.

For several years, Mastromonaco has considered artificial insemination using sex-sorted sperm to increase the number of females in wood bison herds such as the one at the Toronto Zoo.

While the scientists can only estimate the bison cow’s due date in late October, they already know that her fetus is a female.

“Females are more valuable in wood bison, especially in zoological or conservation herds,” explains Dr. Eric Zwiefelhofer, a postdoctoral fellow working with reproduction specialist Dr. Gregg Adams at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM) and Mastromonaco at the Toronto Zoo.

“A male can naturally breed 20 to 30 cows a year and can have 20 to 30 offspring; however, a female has only one offspring per year. The females are the limiting factor.”

Mastromonaco’s idea for investigating the sex-sorting technology as an addition to wood bison conservation breeding programs was finally realized in 2020 when the Toronto Zoo contributed matching funds for Zwiefelhofer’s postdoctoral fellowship through the Mitacs Elevate program. The not-for-profit research organization works in partnership with Canadian universities, private industry and government to operate research and training programs in industrial and social innovation fields.

Working with Adams and members of the USask Bison Research Group, Zwiefelhofer also teamed up with Dr. Clara Gonzalez-Marin from STGenetics. The Texas-based company is the leader in sperm sex-sorting technology with the equipment and media to provide sperm sorting services for almost all mammalian species.

“It is very exciting when we get the opportunity to work with any new species, and especially when those projects involve restoring genetic purity and diversity among threatened populations,” says Gonzalez-Marin.

Working with fresh semen collected from three wood bison bulls at the USask facility, the research team at STGenetics selected the ejaculates with the highest sperm quality and set up the protocols necessary to process, sort and isolate the X-chromosome bearing (female) sperm. The sex-sorted sperm was then placed into straws at the appropriate concentration, cryopreserved and shipped to Saskatoon, Sask.

A second batch of semen (the conventional unsorted semen) was collected from wood bison bulls at the Toronto Zoo where it was extended, frozen and shipped to the USask research team.

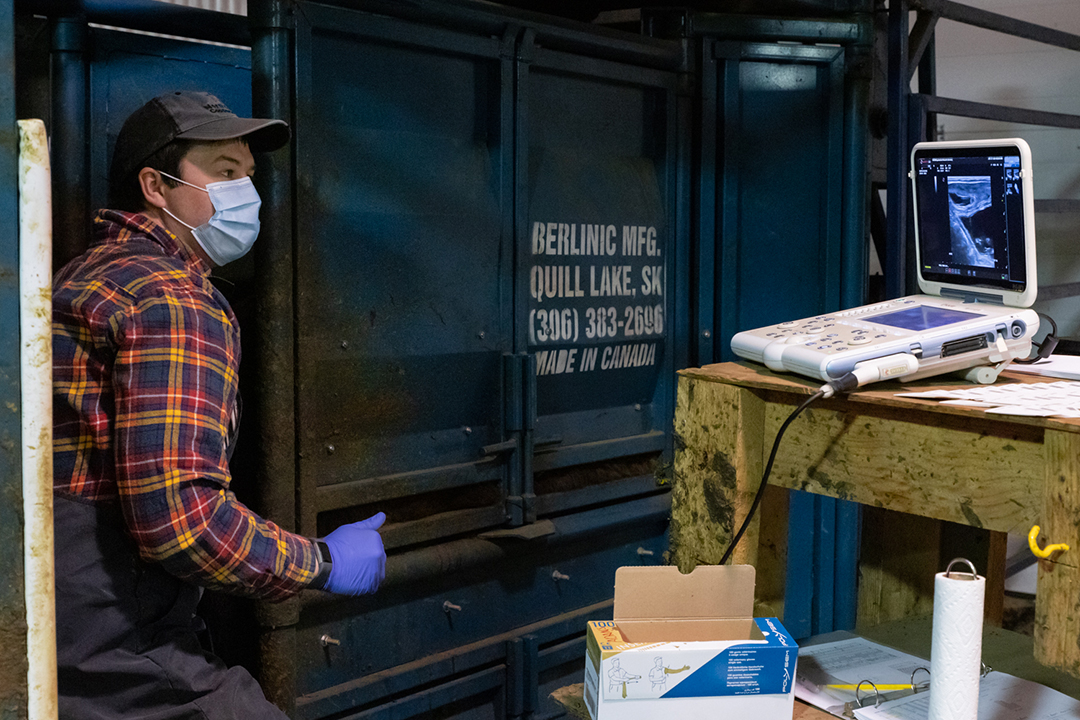

Using protocols for fixed time artificial insemination (FTAI), Zwiefelhofer timed the artificial insemination near ovulation for optimal fertilization in 26 wood bison cows. Each female was randomly inseminated with one unit of either the sex-sorted or the conventional semen.

Thirty days later, ultrasound exams revealed three conventional pregnancies and one sexed pregnancy. The researchers attribute the lower pregnancy rate to the extremely cold weather in Saskatchewan during the synchronization and FTAI process.

Although the researchers knew they had one sexed pregnancy, they had to wait another 30 days before ultrasonography indicated that the sex-sorted sperm pregnancy was a female.

The study results are significant since they confirm that the sex-sorting technology can be effective for increasing the number of female wood bison in conservation and zoological herds as well as in free roaming herds.

In addition to this reproductive achievement, the researchers from USask and the Toronto Zoo were the first in the world to produce wood bison calves born using in vitro fertilization. They were also the first research team to produce bison calves from frozen, in vitro embryos produced from immature eggs that were collected from live bison.

Zwiefelhofer is planning a subsequent study that will combine sorted sperm with eggs from wood bison to produce a female in vitro fertilized embryo.

“We could take that embryo and either transfer it into our herd at USask or other conservation herds throughout Canada,” says Zwiefelhofer. “If we were able to collect sperm from [bison in] Alberta and eggs from a [bison] herd out in Québec, we can combine them in the lab and produce an embryo. We’d be able to move these genetics around in a biosecure manner without having to move live bison.”

This fall, Zwiefelhofer will also undertake a second artificial insemination breeding trial using a larger number of bison cows — an opportunity to increase the pregnancy rate by using FTAI earlier in the breeding season and by adjusting synchronization protocols and timing of insemination.

Although Zwiefelhofer grew up on a dairy farm and has had extensive experience working with cattle reproduction, he particularly enjoys the challenge of working with bison — a wild species with little known about its reproduction.

“You always want to improve, and it’s the challenge, the uncertainty of some of the research that we do,” says Zwiefelhofer. “At the end of the day, I enjoy seeing calves being born from our technology … we’re able to use these technologies and apply them towards a threatened or endangered species for future generations, and that’s rewarding.”

For Mastromonaco, the sex-sorting study’s successful outcome provides another tool in the conservation toolkit. The research project also reinforces the importance of partnerships to tackle the challenging issue of protecting the wood bison species from extinction.

“Partnerships are the foundations for successful species conservation outcomes,” says Mastromonaco. “There is not enough time or money to save all the species, so it is important to build the right teams to ensure that goals can be met in a timely manner.”