Can we increase reproductive lifespan?

Reproduction relies on the continuous self renewal of stem cells in the germ line to replenish the stocks of eggs and sperm. How long an organism will be able to reproduce during its life (reproductive life) and how fertile it will be during this time (reproductive capacity) depend in part on the number of cell divisions that these cells can undergo before deteriorating with age (senescing).

In collaboration with U of S medical researcher Dr. Troy Harkness, Dr. Carlos Carvalho and his team at the U of S College of Arts and Science (Department of Biology) have found that a conserved protein (RER-1 or retention in endoplasmic reticulum protein) controlling the shuttling of cargo within cells (between the Golgi and the ER) regulates lifespan in yeast cells and affects reproductive lifespan in the nematode worm C. elegans. Their findings were recently published in PLOS Genetics.

In the germ line of C. elegans, RER-1 acts as a sensor that reads the normal balance between protein production and degradation. As cells age and become less proficient in getting rid of cytoplasmic debris, RER-1 contributes to signal for the activation of UPR (unfolded protein response) and degradation and recycling pathways known as autophagy.

This leads to several cellular events aimed at reducing protein load. As a consequence, cells remain “healthy” and able to divide further. Worms in this RER-1-induced state of stress are reproductively active in later stages of life compared to wild type worms.

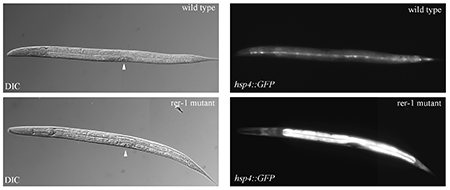

The series of images (below) shows a wild type and RER-1 mutant worms expressing the UPR-marker transgene hsp-4::GFP in intestinal cells. Left are differential interference contrast (light microscopy) images, right are fluorescence images. The hsp-4 promoter is highly trans-activated as a response to ER stress and serve as a marker for the unfolded protein response in worms.