Heartworm

Heartworm prevalence is, overall, low in Canada, with endemic transmission occurring seasonally only in regions of southern British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and New Brunswick.

Testing and preventives are necessary in these areas of Canada where heartworm is endemic, or for pets traveling to or through endemic areas during transmission season. Transmission seasons vary across Canada, but generally range from May to October.

Antigen testing is the primary screening test for heartworm infection in dogs. These serological tests detect antigen produced by adult female nematodes in established infections, about 6-7 months after exposure to the infective mosquito. Veterinarians in endemic areas should evaluate the risk of infection on an annual basis (e.g. compliance in previous year, travel to high risk areas) and make the decision on whether or not to test on a case by case basis.

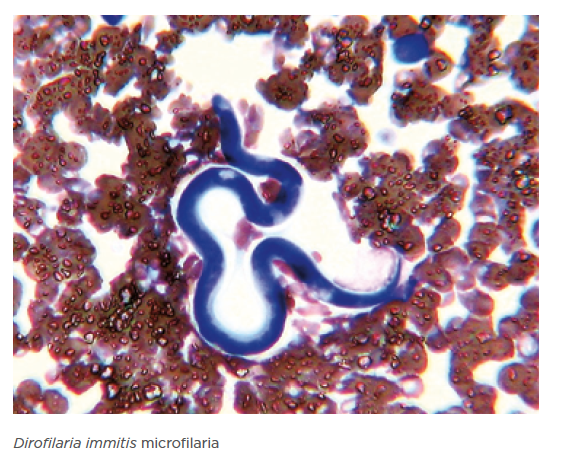

In non-endemic areas, dogs should only be tested if they have a history of travel to or through endemic areas more than seven months previously, bearing in mind that false positives may constitute a large proportion of the positive results. In endemic areas, testing should be performed prior to beginning preventive treatment, and 6-7 months after the last possible exposure to infected mosquitoes in the previous year. Therefore, in Canada, antigen testing should ideally be conducted in spring (April-May). Microfilarial concentration techniques may help confirm infection; however they will not detect occult infections (non-patent infections, i.e. during the pre-patent period, with same sex worm infections, or with senescent worms) and may not detect low levels of microfilaremia. Animals that test positive for antigen but have no microfilaria and no suggestive history (e.g. travel to, or residence in, an endemic region, clinical signs, lack of prophylaxis) should be retested in six months. False negatives are also possible on the antigen test, due to testing too early, or infections with only male nematodes. Heartworm preventives target third stage larvae (L3) acquired from mosquitos and developing fourth stage larvae in the early stages of infection.

Heartworm preventive products are generally macrocyclic lactones administered monthly that kill larvae acquired in the month prior (one month reachback, or retroactive efficacy). Thus, dogs and cats living in or traveling to endemic regions should receive a heartworm preventive starting one month after transmission begins and finishing within one month following the end of the transmission season. For animals residing in Canada that do not travel abroad, this means six treatments per year from June 1st to November 1st. Puppies and kittens in endemic regions should begin heartworm prevention by 8 weeks of age if born during the transmission season. Heartworm preventives are safe and, with good compliance, are usually highly efficacious. However, there have now been multiple reports demonstrating resistance to macrocyclic lactone heartworm preventives in various parts of the USA – most notably the Mississippi Delta region – as well as in one dog imported from Louisiana into Ontario

(Bourguinat et al 2011, Wolstenholme et al 2015).

Dogs diagnosed with active heartworm infections (ideally with an antigen test plus/minus a microfilarial concentration test) should be treated with the adulticide melarsomine dihydrochloride as well as a microfilaricide plus/minus doxycycline (to inactivate symbiotic bacteria), as recommended by the American Heartworm Society. CPEP strongly advises against use of the “slow kill” method (i.e., administering a monthly preventative as a microfilaricide) as it creates the optimal conditions for generating resistance to macrocyclic lactones, which is known to be emerging in canine heartworm. Monthly preventives are designed to kill L3, and may be at a lower dose than that recommended to kill microfilaria (first stage larvae produced by adult heartworms in established infections). Microfilaricides prevent ongoing transmission to mosquitoes. This is important because once heartworm is endemic in a region, it is very difficult to eliminate because not all dogs are on preventive medications. In addition, wildlife such as coyotes, wolves, and foxes can serve as reservoir hosts of heartworm.

The heartworm antigen test and microfilarial recovery techniques do not work reliably in cats due to low heartworm burdens, failure to develop fully to adult nematodes, and transient microfilaremia. Antibody-based serology is an option. Cats may experience respiratory disease, ectopic migration of heartworms with severe neurological signs, and even sudden death. Therefore heartworm prevention for cats should be considered in endemic areas.

Further information on heartworm testing and interpretation is available in the supplemental section of these guidelines and from the American Heartworm Society at www.heartwormsociety.org.

Considerations

Annual testing may be indicated in highly endemic areas even if the dog was on a heartworm preventive during the previous season because:

- All products have reports of lack of efficacy, and resistant heartworm strains may make their way into Canada via importation of dogs (Bourguinat et al 2011).

- There may be compliance issues, missed doses, or undetected vomiting.

- Annual testing ensures early and timely detection of a positive case.

- There is a risk of adverse reaction following administration of some preventives to a heartworm-positive dog.

- Pharmaceutical companies will not cover the cost of adulticidal treatment if pets are not tested annually.