Atlantic Canada

Regional prevalence data for gastrointestinal parasites, heartworm, fleas, and ticks for the Atlantic provinces

Region-specific parasites

- Angiostrongylus vasorum (French heartworm)

- Crenosoma vulpis (fox lungworm)

- Aelurostrongylus abstrusus (feline lungworm)

Gastrointestinal parasites

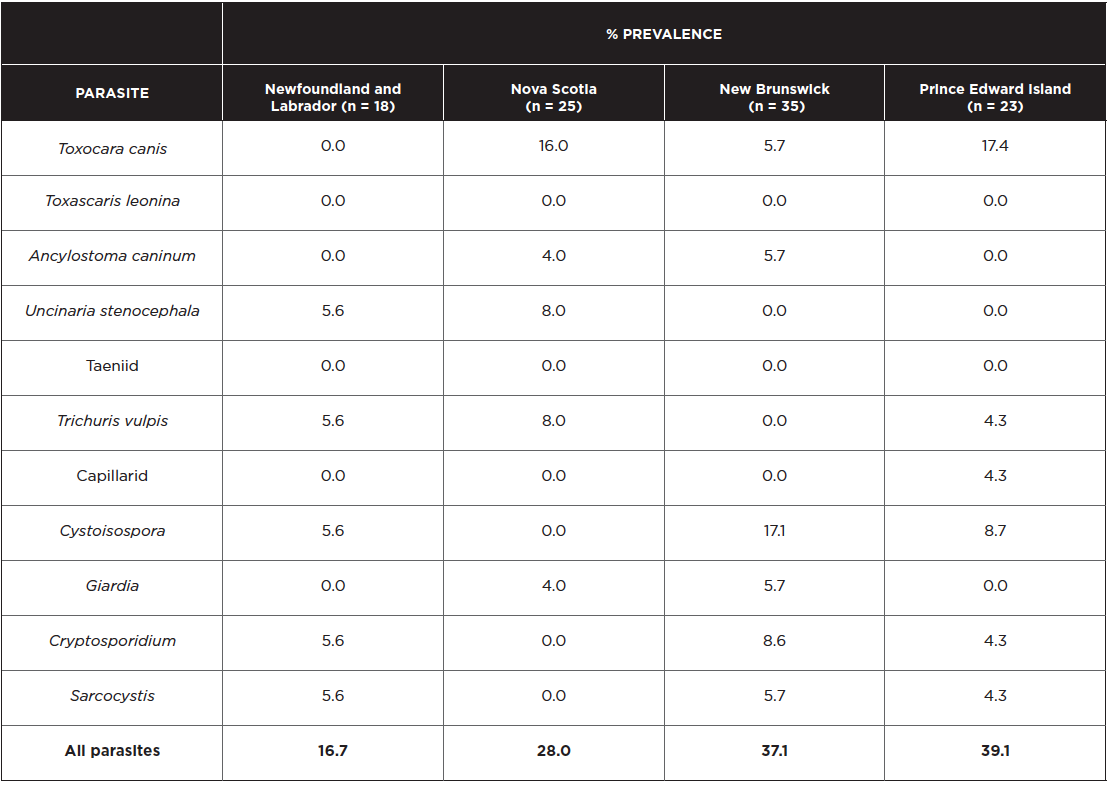

The tables below show fecal flotation data from shelter animals and are therefore not representative of the expected parasite prevalence in pet populations that receive regular veterinary care. However, they do provide information on the types of parasites that pets may be exposed to in this region.

Based on sugar flotations and centrifugation of fecal samples collected from 101 shelter dogs, the most commonly observed parasites in dogs in Atlantic Canada are Toxocara canis, Cystoisospora, and Cryptosporidium (Villeneuve et al 2015). The complete fecal examination results are shown below, with the total number of dogs sampled per province provided in parentheses.

In a study of Prince Edward Island dogs < 1 year old, the prevalence of parasites in client-owned dogs (n=78) was 38% for Giardia, 13% for Cystoisospora, 10% for Cryptosporidium, and 9% for T. canis (Uehlinger et al 2013). The higher prevalence of Giardia and Cryptosporidium noted in these pet dogs compared to the shelter dogs above is likely due to the greater sensitivity of the immunofluorescent detection method used. Three quarters of the Giardia-positive samples belonged to the dog-specific assemblages C and D, while one sixth of samples contained zoonotic assemblage A or B. All Cryptosporidium-positive samples that were sequenced were identified as the host-adapted C. canis.

Based on sugar centrifugal flotations of fecal samples collected from 81 shelter cats, the most commonly observed parasites in cats in Atlantic Canada are Toxocara cati, taeniid tapeworms, and Cystoisospora spp. (Villeneuve et al 2015). The complete fecal examination results are shown below, with the total number of cats sampled per province provided in parentheses.

A study of parasite prevalence in feral cats on Prince Edward Island showed similar results, with T. cati (34%), taeniid tapeworms (15%), and Cystoisospora (14%) being most common in the 78 samples examined (Stojanovic and Foley 2011). A single cat (1.3%) in this study was shedding Toxoplasma gondii oocysts, though seroprevalence was much higher (29.8% of 96 cats).

Heartworm and Lungworms

Heartworm has been endemic in and localized to the Tracadie area of New Brunswick for some time and has not spread, although prevalence monitoring should occur. Monthly preventive should be administered from June 1st to November 1st.

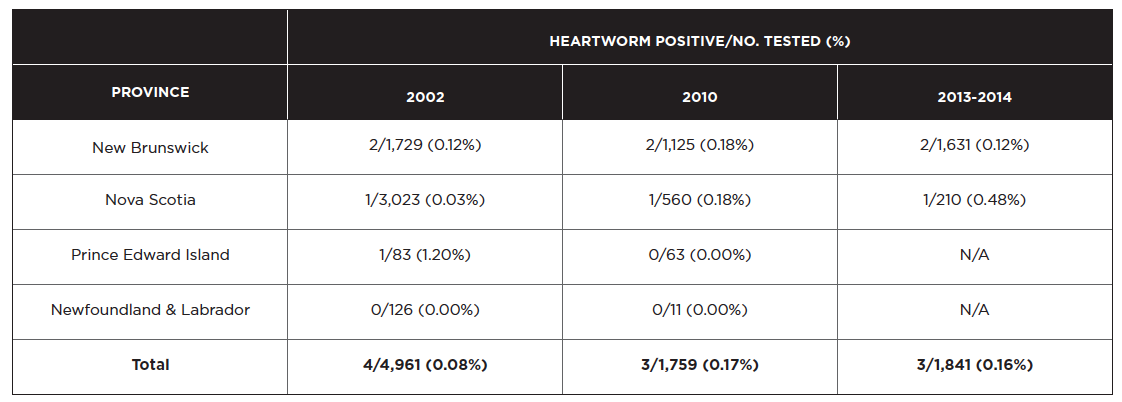

The last systematic postal survey of heartworm in Canada was carried out in 2010. Of the 564 canine cases diagnosed, three cases were in the Maritimes: one dog in Nova Scotia, and two dogs in New Brunswick. The survey data for Atlantic Canada are presented below alongside the postal survey from 2002 and IDEXX SNAP 4Dx data from 2013-2014 (Herrin et al 2017). Because the 2013-2014 SNAP 4Dx test results are not accompanied by information on confirmatory testing, we cannot draw firm conclusions when comparing this data to veterinarian-diagnosed cases from prior years. However, it does provide an estimate of heartworm prevalence that can help to establish a temporal trend.

While the total number of heartworm cases diagnosed in Canada has increased since 2002, prevalence within the Atlantic provinces has remained relatively steady. There is an apparent rise in prevalence in Nova Scotia, however, the single case diagnosed in 2010 was an imported dog, and the travel history of the case from 2013-2014 is unknown. Veterinarians are advised to remain vigilant, particularly for dogs imported from heartworm-endemic regions.

Dogs in Atlantic Canada can also be infected with Crenosoma vulpis (the fox lungworm) and Angiostrongylus vasorum (the French heartworm). {» FOR MORE INFORMATION SEE THE SUPPLEMENTAL SECTION ON METASTRONGYLID LUNGWORMS / PG. 51} The prevalence of C. vulpis in dogs in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Newfoundland is unknown, but the parasite is highly prevalent in the red fox population (50% to 90%). On Prince Edward Island, post-mortem data from Humane Society cases shows that 3% of the general dog population has this lungworm (Bihr and Conboy 1999). A similar rate is likely in Newfoundland. Based on fecal diagnostics, about 20% of dogs in Atlantic Canada suffering from chronic coughing are infected with C. vulpis (Conboy 2004).

Reports of A. vasorum in dogs are mainly restricted to southeastern Newfoundland, where 11% of shelter dogs had adult worms in their pulmonary arteries upon necropsy (Bourque et al 2008). Roughly a quarter of dogs with chronic cough in this region are infected with A. vasorum (Conboy 2004). Recently, a case of A. vasorum-associated paradoxical vestibular syndrome was reported from Codroy, on the western coast of Newfoundland (Jang et al 2016). This dog had no history of travel outside of western Newfoundland, suggesting that A. vasorum has now spread across the island. This hypothesis is supported by the results of an unpublished survey showing A. vasorum infection in foxes throughout Newfoundland, even northern regions. A. vasorum is a potentially serious pathogen that causes permanent damage, and as such, warrants regular anthelmintic prophylaxis while the mollusc intermediate hosts are active (typically from mid-April through October, sometimes up to December). Monthly moxidectin or milbemycin are suitable for this purpose.

In a recent study, researchers from Acadia University and provincial wildlife biologists found A. vasorum infection in coyotes in 4 different counties in Nova Scotia indicating that French Heartworm has successfully spread to the mainland (Priest et al, 2018). Presumably after a period of expansion within the wild canid population (especially red fox) infections are expected to occur in dogs. As with C. vulpis, the large red fox population and the abundance of gastropod intermediate hosts will likely result in a significant exposure risk to dogs in the Maritime provinces and beyond.

Cats in Atlantic Canada can also be infected with Aelurostrongylus abstrusus (the feline lungworm). This parasite was previously reported from Newfoundland and Labrador. More recently, in an investigation of anesthesia-related feline deaths in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, A. abstrusus was diagnosed in one cat (unpublished).

FOOTNOTE: Priest JM, Stewart DT, Boudreau M, Power J, Shutler D. First report of Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in coyotes in mainland North America. Vet Rec December 2018 (doi: 10.1136/vr.105097)3

Fleas

There has been only a single published report of flea prevalence on Prince Edward Island, where 9.6% of feral cats showed evidence of flea infestation (Stojanovic and Foley 2011). Based on their own experience, veterinary practitioners in Atlantic Canada assess the prevalence as relatively high.

Fleas are not typically a problem year round. The risk period is typically May to October. However, some households have experienced flea problems throughout the year (e.g. unoccupied and infested apartments).

Ticks

Ticks are encountered in most of Atlantic Canada. Ixodes scapularis have been recovered from dogs and occasionally cats, as well as from people, in all Atlantic provinces. I. scapularis is the primary tick in Prince Edward Island, although the overall risk of ticks is low. Other Ixodes spp. ticks have been recovered from both dogs and cats. Dermacentor variabilis is the primary tick in Nova Scotia, particularly in the Annapolis Valley, and in New Brunswick, in areas with the right habitat. Rhipicephalus sanguineus is present at low levels. I. scapularis and D. variabilis activity follows a bimodal pattern with peaks in May/June and again in October/November. Realistically, tick control programs should be used for the whole season.

Maps of Lyme disease risk areas are generated by public health agencies and are available through the links below.

New Brunswick: www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/ocmoh/cdc/content/vectorborne_andzoonotic/lyme/risk.html

Nova Scotia: www.novascotia.ca/dhw/CDPC/lyme.asp

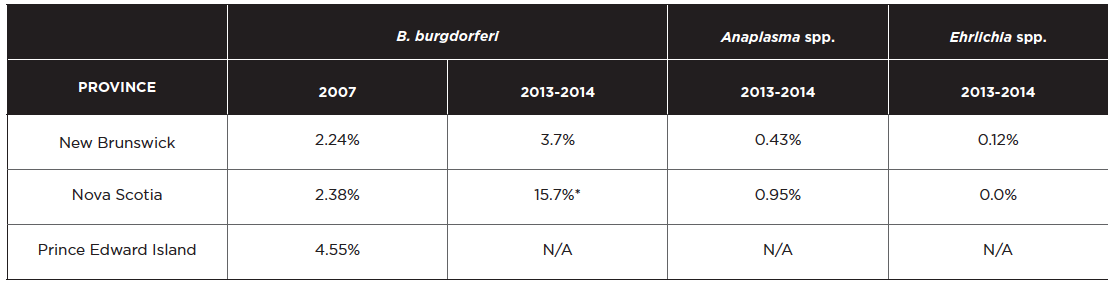

Data from a total of 115,636 Canadian dogs tested in 2013-2014 (Herrin et al 2017), compared to 94,928 samples in 2007 (from Incidence of Heartworm, Ehrlichia canis, Lyme Disease, Anaplasmosis in dogs across Canada as determined by the IDEXX SNAP® 3Dx® and 4Dx® Tests – 2007 National Incidence Study Results, IDEXX, Markham, ON) indicate that seroprevalence of tick-borne agents was as follows:

*A hyperendemic focus exists in Pictou county, where seroprevalence is 40.6%.

These data should be interpreted carefully as they indicate exposure and not current infection. Many dogs that seroconvert for B. burgdorferi do not develop clinical signs. The true prevalence of exposure may be lower than the reported estimates for several reasons: there is no evidence that confirmatory tests were done for any of the samples; the travel history of dogs is not given; and, in light of the very low prevalence of infection in most areas, some positive results may be false positive.