Wheat Quality Management: Lessons from Australia

The developments in Australia beg three questions for policy makers engaged in the current review of the Canada Grain Act. If the CGC activities are curtailed, will industry goods related to quality assurance still be delivered at an adequate level? If so, what organizations will perform these functions? Perhaps most importantly, who will fund these activities in a sustainable manner?

In an effort to modernise the regulatory framework of the Canadian grain industry the Canada Grain Act is currently under review. Since the last review of 1985, the grain industry has undergone significant changes, most notably the removal of single desk marketing powers of the Canadian Wheat Board (CWB) in 2012. This review takes place in the context of an increasingly competitive international market, the changes in the broader quality management system, and changing roles and incentives within the grain marketing value chains. The question is to how regulations could be amended to effectively and efficiently meet current industry needs in a highly competitive environment.

One critical consideration of the review is its effect on the perceived quality of Canadian grains. The Canada Grain Act gives the Canadian Grain Commission (CGC) the authority and the resources that enable it to provide a number of industry goods related to grain quality. In addition to its direct role in variety registration and in management and enforcement of grading standards, the CGC interacts regularly with other organizations and industry stakeholders that impact grain quality. Until 2012, the CWB also played a central role in quality management, not only through direct activities in marketing, logistics and customer service, but also through its funding for the Western Grains Research Foundation and for the Canadian International Grains Institute (Cigi). Many of these activities are currently performed by other industry players including the private grain trade, the newly established provincial Wheat Commissions, and new funding model for Cigi.

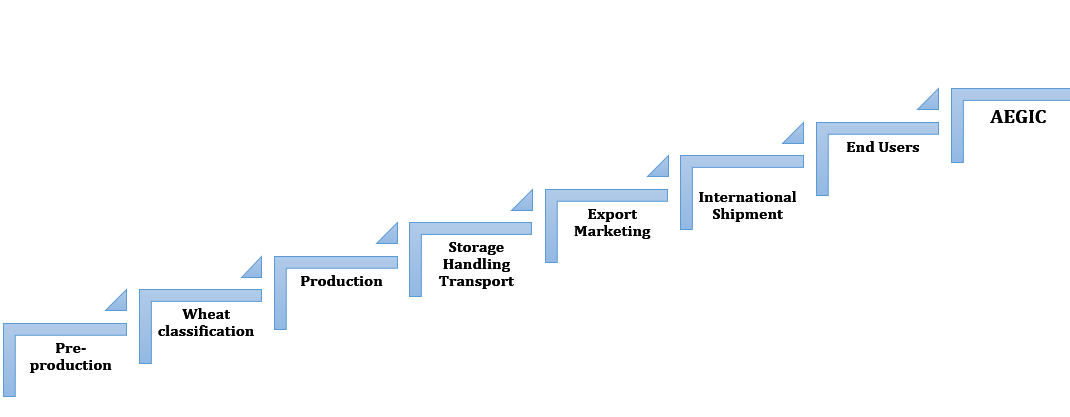

Focusing on the critical importance that other industry goods play in achieving a well-functioning quality assurance system, we draw some lessons from the Australian case. Australia followed the deregulation path earlier than Canada and had to redevelop new organizations to carry out valuable industry functions. Until 2008 the Australian Wheat Board (AWB) played a central role in quality assurance and provision of numerous industry goods. In addition to administering the classification system and variety registration and publishing the trading/grading standards, the AWB was deeply involved in market development and analysis, market intelligence and feedback to breeders, technical training of end-users, all of which enhance and maintain the reputation of a quality product. Under the single-desk regime, the adequate provision and funding of these complementary industry functions was easily achieved within AWB’s centralized structure.

After the elimination of AWB, new organizational and institutional arrangements were needed to fill the void of providing industry goods pertaining to quality. They were relatively fast to emerge for industry goods that were deemed critically valuable by all industry players. These include maintaining the integrity of classification, which has been administered by the Wheat Quality Australia (WQA) since 2012. Additionally, without any governmental directive, publication and administration of the Trading Standards was taken over by Grain Trade Australia (GTA), whose core mission is to facilitate grain trade. While GTA membership is open to all firms operating in the grain industry, membership tiers would place bulk grain handling and marketing companies as significant players.