Introduction

These guidelines are the consensus opinion of the Canadian Parasitology Expert Panel (CPEP) which is comprised of Canadian and Canadian-based veterinary parasitologists and veterinarians in general practice with specific interest or expertise in parasitology in their region.

The guidelines are intended to provide Canadian veterinarians and dog and cat owners with information about the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of parasitic infections including gastrointestinal helminths, heartworm, fleas, and ticks. These guidelines replace the first edition, developed in 2009.

As an additional resource, short summaries of the most common parasites found in Canada have been provided. This new supplemental section presents an overview of life cycle, diagnosis, and treatment options, and includes parasites (e.g. protozoa, mites) not covered in the general management guidelines. Also included are special considerations for specific populations, such as northern, rural and remote dogs, and specific parasites that may be emerging (ticks, tapeworms) or require special management.

In preparing the guidelines, CPEP took into account the most recent Canadian data – and informed opinions where data do not exist – on the prevalence and distribution of parasites of veterinary and public health importance. Where possible, we considered regional differences in parasite transmission when determining the optimal frequency for antiparasitic treatments. Transmission of vectors and vector-borne parasites (such as fleas and heartworm) is seasonally limited for many regions of Canada. For many gastrointestinal parasites, the potential for transmission is greatly reduced during the winter months. Therefore, treatment and control measures for ectoparasites, vector- borne parasites, and directly transmitted gastrointestinal parasites are often focused on spring, summer, and fall in Canada. We recognize that environmental change may be altering the length of seasonal transmission periods, and that continued surveillance (diagnostic testing) and predictive modeling are needed to detect and proactively address such changes.

Veterinarians should use the available data together with their local knowledge to apply and align these guidelines to the realities of their practice. Veterinarians may recommend altered treatment schedules based on an assessment of a pet’s risk factors such as age, lifestyle, location, health status, and individual needs, as well as the composition of the household (children, pregnant, or immunocompromised people) and the risk tolerance of the client. We continue to emphasize the importance of a good history and diagnostic testing to guide appropriate and individualized treatment plans, to detect the emergence of new parasites or anthelmintic resistance, and to incentivize owners to see their vet at least annually.

The major objectives of all treatment and control programs are to remove harmful parasites, to prevent their establishment, to reduce environmental contamination with life cycle stages that can infect other animals and people, and to minimize the development of drug resistance in parasites. Veterinarians should follow label instructions for parasite treatment and control when approved products are available.

Evidence-based parasite diagnostic and control programs have positive effects on pet health and play an important part in the prevention of zoonoses. These guidelines will aid veterinarians to inform pet owners about the health implications for their pets, and, in some cases, for human health. Ongoing discussion with clients is key to compliance and implementation of prevention, treatment and control programs that can reduce parasite burdens in dogs and cats and transmission of zoonotic parasites. This can be incorporated into annual health examinations, which should include regular diagnostic monitoring for vector-borne and fecal parasites.

Veterinarians can also reinforce public health messages such as:

- Washing hands (particularly children’s) with soap and water after outdoor activities, handling pets, pet feces disposal and before meals.

- Wearing gloves while gardening.

- Thoroughly washing produce from backyard gardens prior to consumption.

- Promptly removing and properly disposing of pet feces.

- Limiting pet defecation areas. + Reducing pet interaction with stray and wild animals.

- Preventing wildlife access to buildings used by pets and people.

- Covering sandboxes when not in use.

- Checking for ticks after being outdoors in endemic areas.

Protocol

Treatment

Treat puppies and kittens every 2 weeks starting at 2 weeks of age. At 8 weeks, switch to a monthly schedule. From 6 months of age onward, monthly or regular targeted treatments can be given based on the pet’s individual risk.

Under six months

Puppies and kittens less than six months of age:

Puppies and kittens should ideally be treated with an anthelmintic with activity against Toxocara spp. at two, four, six and eight weeks of age, and then monthly to six months of age. This early start schedule ensures removal of Toxocara spp. acquired prenatally and/or through the milk. Because most puppies and kittens do not have contact with a veterinarian until six to eight weeks of age, it may be necessary to provide anthelmintics to breeders for earlier treatments. Nursing bitches and queens should be treated concurrently with their offspring since they often develop patent infections along with their young (Sprent 1961, Lloyd et al 1983). When puppies or kittens are first acquired by their owner, they should be dewormed for a minimum of two treatments spaced two weeks apart and then monthly up to six months of age; three initial treatments at 2-week intervals may be used to synchronise deworming with vaccination programs. Fecal parasitological examinations should be performed twice in the first 6 months of the animal’s life (e.g. at 2-3 months and 6 months of age). The choice of product and scheduling of future treatments should be based on the parasites detected and their prevalence in a given geographic area.

Over six months

Dogs and cats over six months of age:

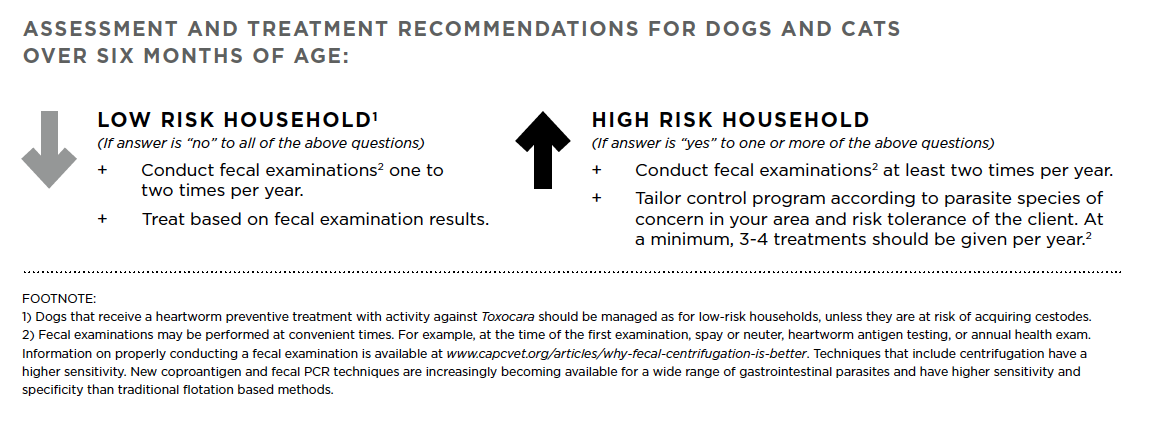

All dogs and cats over six months of age should have at least 1-2 fecal parasitological examinations per year and be assessed for risk of parasitic infection. Decreased anthelmintic use can be justified for pets who are regularly tested and are considered low risk animals. Veterinarians should consider the pet’s lifestyle, location, health status, composition of the household, and ask pet owners the following questions to assess the animal’s risk level:

- Are there young children in the house? In regular contact with the animal?

- Are there individuals with compromised immune systems in the house? In regular contact with the animal?

- Are there any pregnant women, or women who could be pregnant, in the house? In regular contact with the animal?

- Is the dog or cat a service animal?

- Do pets frequently come into contact with highly contaminated environments (e.g. dog parks, kennels)?

- Do pets have access to wildlife such as rodents, rabbits, birds, or carcasses of livestock or wild cervids?

- Do pets ever roam freely?

- Are pets fed raw meat or organs?

Fecal testing

Veterinarians may sometimes choose to forgo fecal diagnostic testing because their patient is already on an anthelmintic regimen (e.g. monthly heartworm preventive) or because of client financial constraints, among other reasons. However, it is important to recognize that regular fecal monitoring (at least annually) is still indicated because fecal testing:

- Can help tailor the choice of anthelmintic treatment and prophylaxis for individual animals and regions.

- Can detect developing anthelmintic resistance (as is already seen with heartworm and gastrointestinal nematodes of large animals).

- Can reduce the unnecessary use of anthelmintics in low risk animals, low risk households, and low risk regions.

- Can help detect other parasites, including cestodes such as Echinococcus, Dipylidium, and Taenia spp., and protozoans such as Cystoisospora, Giardia, Cryptosporidium, and Sarcocystis species.

- Can help detect emergence of new parasites in new regions, key in an increasingly globalized world and an increasingly permissive climate.

- Is most useful if done well (centrifugation methods), performed by trained personnel, and interpreted by diagnosticians familiar with regional parasite fauna and accompanied by a detailed history including travel (even locally), animal behavior (risk factors such as diet, coprophagia) and detailed parasiticide treatments (type, frequency, compliance).

- Will become increasingly sensitive and specific as new PCR-based and coproantigen technologies are emerging.

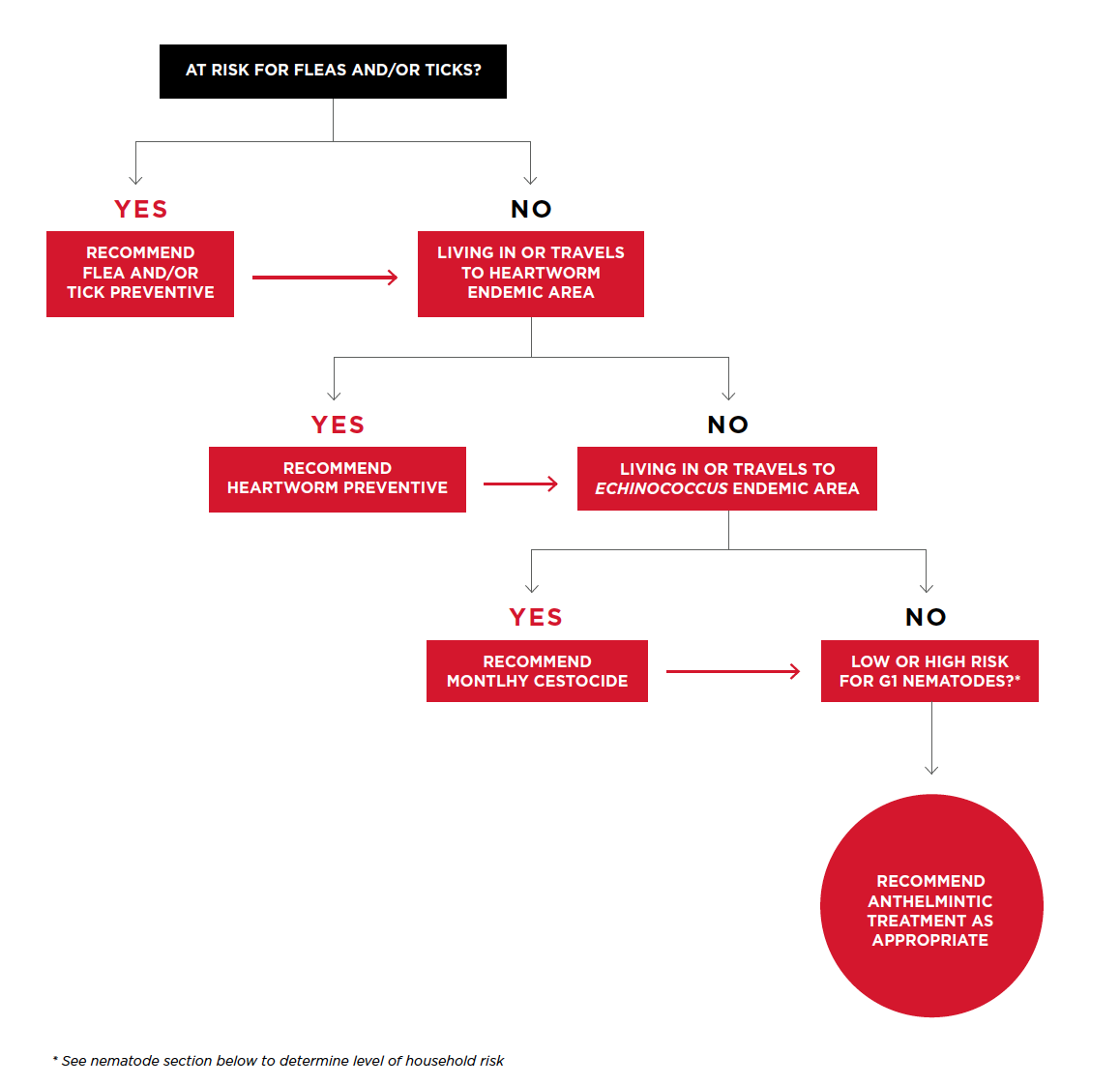

All dogs and cats should be assessed for risk of parasitic infection, including gastrointestinal helminths, heartworm, fleas, ticks and protozoans based on regional knowledge of parasites, interviewing clients, and, whenever possible, by using appropriate diagnostic testing.

The following flowchart will help veterinarians determine the most appropriate treatment and prevention regimen for their patients based on an individual patient risk assessment.

Data

Veterinarians should note that in some areas these data are limited and/or dated. To fill these gaps, Canadian Parasitology Expert Panel (CPEP) members have provided their impressions of prevalence based on their diagnostic experience and discussions with local veterinarians. Therefore, the data should be considered as guidelines for veterinarians and not a precise measure of parasite occurrence. In addition, parasite prevalence and species composition can be expected to vary with location, a pet’s lifestyle and its level of veterinary care. Veterinarians are encouraged to use the information provided here in conjunction with their own local knowledge when making decisions about parasite diagnosis, treatment, and control.

Note: Heartworm transmission start and end times are taken from Slocombe et al. 1995, and are based on the concept that heartworm microfilariae require 14 days at the minimum threshold temperature of 14°C to complete development to the infectious third larval stage within mosquitoes. An assumption is also made that infected mosquitoes are not able to survive the winter. These regional transmission dates can be used to provide general guidelines on choosing start and end times for preventive use. However, these dates are based on temperature data for 1963-1992, now considered a baseline period for current climate projections. Canada continues to experience warming due to climate change (a mean annual warming trend of 1.7°C nationally since 1948, with the most rapid warming in northwestern Canada); therefore, the transmission season likely begins earlier and ends later than the dates presented below.

Parasites

Due to climate variations across the country, Canada has highly variable distributions and abundance of fleas, and multiple species of fleas, some of which primarily infest dogs and cats, while others only temporarily infest dogs and cats in contact with wildlife. Infestations of dog and cat fleas are primarily maintained in the environment.

In tick-endemic regions, veterinarians should remind pet owners of the following measures to avoid ticks and tick-borne diseases, in the following order, according to risk of the pet and risk perception of the owner.

- The first line of defense is avoidance; litter under forest canopies, overgrown grass and brush in yards, especially during periods of high tick activity (seasonally and diurnally).

- Second is regular checking and removal of ticks from pets and people within 6-24 hours of being in tick-infested areas.

- Wearing protective clothing such as long pants, long sleeves and socks will help prevent tick attachment to people.

- To remove an attached tick, use tweezers to grasp its “head” and mouth parts as close to the skin as possible. Pull slowly until the tick is removed. Do not twist or rotate the tick and try not to damage or crush the body of the tick during removal. After removing the tick, wash the site of attachment with soap and water and/or disinfect it with alcohol or household antiseptic. (Reference: www.canada.ca/ en/public-health/services/diseases/lyme- disease.html)

- Third, there are a wide range of tick control products for high risk dogs and repellents for people. Permethrin treated clothing may also be an option for high risk people.

- Finally, high risk dogs can also be vaccinated against B. burgdorferi, consistent with recommendations of the ACVIM.

Treatment and management of B. burgdorferi positive dogs should be conducted in accordance with the ACVIM Consensus Update on Lyme borreliosis in Dogs and Cats (2018) in conjunction with the original ACVIM Consensus Statement on Lyme Disease in Dogs: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention (2006).

There are a wide range of gastrointestinal nematodes, including ascarids (Toxocara, Toxascaris, and Baylisascaris spp.), hookworms (Uncinaria and Ancylostoma spp.), and whipworms (Trichuris spp.), present in companion animals across Canada, and there are strong regional differences in prevalence.

Heartworm prevalence is, overall, low in Canada, with endemic transmission occurring seasonally only in regions of southern British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and New Brunswick.

Risk of exposure to cestodes should be assessed through a good history (focusing on flea control, diet, and access to wildlife and fish intermediate hosts) and through fecal diagnostic testing (although false negatives are common using fecal flotation methods, there are new fecal PCR and coproantigen methods that offer potentially higher sensitivity).

Information

Tick encounters have become increasingly common in eastern Canada due to the northerly expansion of Ixodes scapularis (also known as the blacklegged tick, or deer tick).

Zoonotic Echinococcus spp. tapeworms are emerging as a cause of canine and human disease in Canada.

The regular use of anthelmintics has led to widespread drug resistance in many gastro-intestinal nematode species of grazing livestock and horses (Kaplan and Vidyashankar, 2012).

Dog and cat populations in rural, remote, and Indigenous communities have special issues regarding parasite fauna and management of parasites.

Many parasites that occur abroad are not seen, or very rarely, in Canada and several of them are major diseases transmitted by arthropods.

News

Loading...

Experts

Canadian Parasitology Expert Panel (CPEP)

Dr. Gary Conboy, Professor of Pathobiology and Microbiology, Atlantic Veterinary College, Charlottetown, PEI

Dr. Christopher Fernandez Prada, Assistant Professor of Parasitology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Université de Montréal, St-Hyacinthe, QC

Dr. John Gilleard, Professor of Molecular Parasitology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB

Dr. Emily Jenkins, Associate Professor, Veterinary Microbiology, Western College of Veterinary Medicine, Saskatoon, SK

Dr. Ken Langelier, VCA Canada Island Animal Hospital, Nanaimo, BC

Dr. Alice Lee, Assistant Professor of Parasitology, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA

Dr. Andrew Peregrine, Associate Professor of Parasitology, Ontario Veterinary College, Guelph, ON

Dr. Scott Stevenson, Thousand Islands Veterinary Services, Gananoque, ON

Brent Wagner, Department Assistant, Veterinary Microbiology, Western College of Veterinary Medicine, Saskatoon, SK

Sponsors